|

|

|

|

|

||

Confessions of an Incorrigible Comic Book Collector

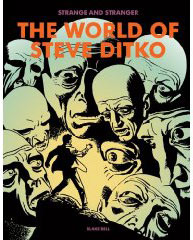

When a Minnesota contractor dug the first appearance of Superman out of the insulation of his home in 2013 he scored a $175,000 windfall, more than 15 times what that fixer-upper cost him. His copy of Action Comics #1 would have gone for a lot more if one of his grabby in-laws hadn't torn the back cover, downgrading it from Fair to Poor condition. The debut appearance of Ant-Man from 1962 recently sold for $200,000. Ant-Man! In 1965 I plucked my first comic book from a spinning rack in the curved corner window of Edmund's Drug Store in the Plaza Shopping Center (Pastabilities is there now). It was 80 Page Giant #10, a collection of darkly disturbing stories with Superman as a youngster being menaced by an evil doppleganger, emasculated by a criminal from the future, hunted like an animal, sadistically tortured by the Kryptonite Kid and his rabid green glowing mutt. This eight-year old was hooked, couldn't wait to mail a dollar off to DC for a year's subscription to Superman, even as my parents assured me I'd never see that money again or ever receive anything for it. An early indication they were as full-of-it as I suspected. After a few weeks those four color adventures began arriving monthly, folded in a brown paper sleeve. I read breathlessly as The Man of Steel was forced to reveal his secret identity to the world, robbed Fort Knox, was exorcised as a demon, then bested in combat by a female ("Great Krypton! I never dreamed it could happen!"). A twist ending assured readers the status quo had never seriously been threatened, nor would it ever be. In the sixties and seventies collecting comics, mostly a guy thing, was just about the most deplorable activity a teenager could get involved with. There were parents, no doubt, who would rather have discovered their son had joined a gang or was caught torturing small animals. At best, comic books were regarded as an easy way to keep children quiet when they're down with the flu or on a road trip. In many homes they were expressly forbidden by parents who were unwitting victims of a political disinformation campaign in the 1950s that convinced a large swath of the public that those cheap pulp fantasies were depraved, mind-rotting filth responsible for a generation of juvenile delinquents, the kind you mostly only saw on TV. (If comics had the advertiser base television had in the fifties they would have been required reading.) As a pre-teen in the late 1960s, at an age when one would be expected to put away the funny books and pick up some real ones, a flood of young writers and artists emerged, re-imagining the art form just as Stan Lee and Jack Kirby were parting ways at Marvel Comics. Newcomers and old pros alike went about reinventing the very notion of graphic storytelling. Comics matured in lockstep with baby boomers, providing the scaffolding for today's multi-billion dollar superhero movies built around characters, storylines, even specific images from that era. For whatever reason, in Greensboro comic books were distributed a month later than they were anywhere else, and spottily so. Being a completist meant considerable legwork if you didn't want to miss an issue or needed to find copies that weren't bent at the spine after kids had flipped through a stack. New releases hit 'the stands' on Tuesdays and Thursdays, after Irving Park Elementary let out I'd walk to Crutchfield-Browning Drug Store in the Lawndale Shopping Center. If I arrived before Doris Collins had time to do it I'd untwist the metal bands that bundled that day's periodicals—magazines, newspapers, comics—then check them off against a list of what the store was expecting that day. A few doors down Franklin Drugs had two spinner racks with rows of magazines and paperbacks buttressed along a handrail surrounding the downstairs stairway to their toy department. On weekends a journey to find missing issues began at the Bishop Block Drug Store, continued south on Elm to an alcove left of the O.Henry Hotel's front door, inside the furthest back window at Woolworths, then West Market Street Newsstand (next to Stumble Stiltskins) where you could find illustrated magazines like Vampirella and Web of Horror. A breakthrough came in 8th grade when a classmate who worked Saturdays at Sam & Max's Newsstand (319 South Elm) told us we could buy our comics there in spite of the strict 'No One Under 18' policy mandated by an enormous collection of porn magazines they traded in, waist high piles of the most explicit smut imaginable, to say nothing of the peep shows in the back. But Sam & Max's had all the comic titles anyone could possibly want without fail; getting away with selling all those dirty magazines, presumably, by stocking every single publication in the nation, from Better Homes & Gardens to Popular Mechanics to Daddy Spanks His Bad Little Girl. That groundswell of creativity continued in the comics industry well into the late-seventies. The next decade brought forth another fresh crop of innovators, led by Frank Miller and Alan Moore, who lifted the medium to even greater heights. The excitement continues... The cover wore off eons ago but I still have that first double-sized comic book I brought home in 1965, when Superman was a blue-haired guy in his forties with little appetite for settling down and a wandering X-ray eye, who's greatest flaw was an unhealthy desire to be the smartest, strongest guy in the room. If that's not a metaphor for the American experience I don't know what is. |

|

Get it here! SAVE MONEY |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

It's astonishing to me that comic book collecting has taken on a whiff of respectability, frequent news stories of a single ten-cent issue selling at auction for multiple millions of dollars could be one reason.

It's astonishing to me that comic book collecting has taken on a whiff of respectability, frequent news stories of a single ten-cent issue selling at auction for multiple millions of dollars could be one reason.