you're looking

for is right here:

Save money!

|

Everything you're looking for is right here: Save money! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

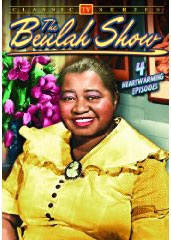

A refreshing and progressive entertainer, Hattie refused to play Beulah with the hyper-exaggerated dialect typified by Marlin Hurt and Bob Corley who came before her. McDaniel fought for, and won, a provision in her contract that included script approval to ensure her role would not be a degrading one. On the new program, it's Beulah's family, her house, her world - even if she was the employee. ABOUT HATTIE By 1947, Hattie McDaniel was already one of Hollywood's most accomplished film actors. While she was forced to play a succession of supplicant, larger-than-life servants in films like The Little Colonel with Shirley Temple and The Shining Hour with Joan Crawford, Hattie alone was allowed to occasionally portray Negro characters that spoke back to whites. This was unheard of in 1930's media, a first measured step toward social progress that can not be overlooked historically.

Because of this long-standing practice, Hattie found herself on the receiving end of a great deal of criticism from the NAACP and other civil rights organizations. They urged her specifically, and other African-American actors in general, to avoid playing these types of demeaning roles. STORY CONTINUES AFTER THIS AD

But Hattie and the others knew that if they didn't play subservient maids and pop-eyed ninnies, indeed if no black actor ever took these roles again, they would likely be played by whites in blackface (or blackvoice). That was already a time honored tradition in Hollywood. Howls of protest rang out when Hollywood began casting Blacks in Negro roles in the first place - Blacks were taking jobs that could be filled by good white folks! After all, the guys who played the most popular and famous black entertainers of the era (Amos 'n' Andy) were both white, as were 'Negro' stars like Watermelon and Cantaloupe, Molasses 'n' January and other impersonators.

She put it more plainly in another interview, "Why should I complain about making seven hundred dollars a week playing a maid? If I didn't, I'd be making seven dollars a week actually being one." Hattie accomplished what she could within the industry; insisting the word 'nigger' not appear in Gone With the Wind a decade earlier and financially supporting up and coming actors in the community. There might be some argument over whether motion picture studios and broadcasters in 1950 had a responsibility to portray African-Americans in a more positive light given past transgressions. Producers didn't believe audiences would except Blacks in anything other than the lightest of entertainment; their place was singing, dancing and mauling the English language for the enjoyment of all.

In one way, Hattie's real life struggle could serve as an example of the difficulties the household workers she all-too-often played suffered - women who's good humor on the job masked the cold reality of their lives at home. Despondent over the criticism leveled at her by civil rights leaders and frustrated over her inability to land good roles, Hattie attempted suicide in the mid-forties. That suicide attempt didn't make the press, but Hattie was quoted as saying at the time, "Hell can't be anything worse than what I've been living through right now." A lifelong devout Baptist, she began to drink and smoke pot, throwing legendarily lavish parties for her fellow African-American actors.

Hattie found herself back on top after assuming the role of Beulah on November 24, 1947, earning a cool thousand dollars a week for the first season (that would be $10,000 weekly in today's money). CBS's investment paid off, within a year Hattie had doubled the ratings of the original series; this was at the time when radio sitcoms were rapidly losing their audience to TV. The NAACP was pleased that - finally - a black woman was made the star of a network radio program. This was also the first instance since Aunt Jemima fifteen years earlier that a series revolved around an African-American female - and remember, that was a white woman in blackvoice. That's not to say Beulah didn't contain broad characterizations but, as Hattie herself argued, that's the nature of every sitcom. For instance, Ruby Dandridge (mother of Dorothy Dandridge) was heard as Oriole, Beulah's best buddy who worked as the maid next door. Oriole was impossibly shrill, grossly inept and hopelessly ignorant - you would have sworn you were listening to Butterfly McQueen doing Prissy from Gone With The Wind. Beulah's boyfriend Bill (Ernie 'Bubbles' Whitman) was lazy, dumb and unwilling to commit to anything but eating. Also in the cast - Hugh Studebaker and Mary Jane Croft (The Lucy Show) as Harry and Alice Henderson, the shallow, upwardly-mobile suburban family Beulah worked for. The Beulah writers were destined to become influential producers of so many classic TV shows over the next three decades - Sherwood Schwartz (Gilligan's Island, Brady Bunch), Sol Saks (Bewitched), Hal Kanter (Julia) and Howard Leeds (Diff'rent Strokes) were all on the creative staff. Just as Hattie's star was rising on radio, her personal life was disintegrating. She eloped with her fourth husband in 1949, a bisexual interior decorator; four months and tens of thousands of dollars later the marriage was over. (Rumor had it that Hattie was bisexual as well, actress Tallulah Bankhead was reputed to be one of her lovers.) The audience was still gung-ho on Beulah, however. CBS already had Amos 'n' Andy under development for television, they didn't need two 'Negro' programs, so ABC announced plans for a TV version of Beulah to debut in the fall of 1950. It was assumed that Hattie would accept the role, but she passed on the part due to her already hectic schedule.

THE TV

SHOW Beulah became the first ever network television series to star an African-American and the first and last TV program to star an African-American woman until Julia debuted in 1968. Beulah was an overall pleasing sitcom with familiar storylines that mimicked the successful radio format, albeit with an entirely new cast.

A true Diva since the 1920s, Waters was one of the most influential singers of all time, some credit her as being the very first Jazz vocalist. Her seminal hit recordings included Summertime, Stormy Weather, His Eye Is on the Sparrow and so many others. Waters starred in several Broadway hits including Cabin in the Sky and Member of the Wedding and starred in the motion picture versions of those plays as well.

Not a naturally plump woman at the time, (she was once famously known as 'Sweet Mama Stringbean'), Waters had to force feed herself to pack on weight for the role. As an unfortunate after-effect, she eventually hit 375 pounds and would be plagued by obesity related illnesses for the rest of her life.

The NAACP may have praised the radio format, but they were not at all happy with the TV version of Beulah. They accused both Amos 'n' Andy (which came along in 1951) and Beulah of leading to a "conclusion among uninformed or prejudiced peoples that Negroes and other minorities are inferior, lazy, dumb and dishonest." Established African-American stars like Eddie 'Rochester' Anderson (The Jack Benny Program) disagreed. "The Negro characters being presented are not labeling the Negro race any more than Luigi (Life With Luigi) is labeling the Italian people as a whole. Beulah is not playing the part of thousands of Negroes, but only the part of one person, Beulah." Distribution over the struggling ABC network was spotty, and the more contentious Waters was not accepted into the role. Unhappy in the role of a maid, Waters became a tyrant on the set where she and longtime acquaintance Butterfly McQueen openly feuded. After the first season, Percy Harris left the role of Bill, unhappy in a part he saw as something akin to "Uncle Tom." Dooley Wilson (Sam in Casablanca) took over as Beulah's boyfriend for year two - but he quit in disgust as well at season's end. Waters announced that she too would leave the production after the second season because of 'pressing commitments' - but more likely due to the mounting criticism of the series. "I'm not concerned with civil rights, " she confided to a reporter. "I'm only concerned with God-given rights and they are available to everyone!"

Despite her reluctance, Hattie began filming the third season of Beulah in the summer of 1951, while her radio show was on hiatus.

The entire cast of the TV show was overhauled. Ruby Dandridge assumed the role of Oriole from Butterfly McQueen, robbing the public of the opportunity to see McDaniel and McQueen working together for the first time since Gone With The Wind in 1939. Truth was, they didn't like each other - so either McQueen walked or Hattie had her fired, depending on which story you want to believe.

The role of Bill Jackson became more understated for TV as played by Hattie's radio cohort and dear friend Ernest Whitman, the interaction between the two brilliant actors was a joy to watch. That's because Hattie was smiling through some serious pain.

|

Please consider a donation

so we can continue this work!

African Americans

on TV / Classic TV Blog /Amos 'n' Andy Radio Show / Amos

'n' Andy TV show

Mrs. Henderson: "Well, women prefer men with polished manners, don't they Beulah?" Beulah: "You just give me the man, I'll do my own polishin'." On the sixth episode of the TV series, Hattie McDaniel opened with a typical Beulah-ism: "Don't let nobody tell you that I'm in the market for a husband. 'Course, I would be, but they don't sell husbands in a market."

In

1946, Hattie McDaniel was seen in the role of Aunt Tempey in Song of

the South, a Disney film that seemed to look longingly back at the 'happy

days' of slavery. In

1946, Hattie McDaniel was seen in the role of Aunt Tempey in Song of

the South, a Disney film that seemed to look longingly back at the 'happy

days' of slavery.

Song of the South has never been released on DVD or video in the United States but can be found easily in European shops.

Hattie McDaniel had a sister, Etta McDaniel,

who was also an actress that played maids and 'Mammy' roles in The

Thin Man Goes Home, Son of Dracula and dozens of other films.

Amos 'n' Andy - the Beginning / Amos 'n' Andy Radio Show / Amos 'n' Andy TV show

|

|

||||||||||||||